Objetivos. Si bien ya ha sido objeto de estudio en familiares de personas con demencia la relación entre el conocimiento acerca de la enfermedad, el estrés psicológico y las experiencias de cuidados, son varias las cuestiones que aún permanecen sin respuesta satisfactoria. El objetivo del presente estudio ha sido conocer dichas dimensiones en portugueses familiares de enfermos con demencia. De forma complementaria, también se analizó la validez del cuestionario. Si bien en Portugal la escasez de mediciones válidas y fiables en este campo ya ha sido objeto de consideración, la investigación sobre los cuidadores es aún incipiente.

Métodos. Se utilizó una submuestra de conveniencia procedente de un estudio de mayor envergadura en Lisboa. Con este propósito, se evaluó transversalmente a una muestra de 50 cuidadores de pacientes aquejados de demencia (de tipoAlzheimer, vascular y mixta), utilizando el Dementia Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ), el GHQ-12, la escala de Sobrecarga del Cuidador de Zarit, la Positive Aspects of Caregiving Scale y parte del Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly.

Resultados. El 68% de los cuidadores eran mujeres, edad media 51, 7 (DT 13, 9) años. El grado de información y las necesidades relacionadas resultaron ser aceptables. En torno a la mitad de la muestra obtuvo una puntuación GHQ positiva. Las puntuaciones GHQ correlacionaron positivamente con las mediciones de sobrecarga, pero no se encontró asociación con DKQ. La sobrecarga y los aspectos positivos de la función de cuidador no se asociaron con el grado de conocimiento de los cuidadores.

Conclusión. Aunque estos resultados no son extrapolables, el hecho de estar informado no parece proteger del sufrimiento psicológico. Se valoró que estos cuidadores se encontraban en situación de riesgo.

Conocimientos sobre demencia, estrés y experiencias de cuidados en familiares de pacientes con demencia.

(Knowledge about dementia, psychological distress and caregiving experiences in families of elderly demented people. )

Gonçalves -Pereira, M1. ; Papoila, A. 2; Mateos, R. 3

1 Departamento de Saúde Mental, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, FCM – Universidade Nova de Lisboa, UNL;

2 Departamento de Bioestatística e Informática, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, FCM – Universidade Nova de Lisboa, UNL; CEAUL

3 Departamiento de psiquiatría / Universidad de Santiago de Compostela; Unidad de Psicogeriatría C. H. U. S.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Cuidador, demencia, Conocimiento, estrés psicológico, Sobrecarga.

Resumen

Objetivos. Si bien ya ha sido objeto de estudio en familiares de personas con demencia la relación entre el conocimiento acerca de la enfermedad, el estrés psicológico y las experiencias de cuidados, son varias las cuestiones que aún permanecen sin respuesta satisfactoria. El objetivo del presente estudio ha sido conocer dichas dimensiones en portugueses familiares de enfermos con demencia. De forma complementaria, también se analizó la validez del cuestionario. Si bien en Portugal la escasez de mediciones válidas y fiables en este campo ya ha sido objeto de consideración, la investigación sobre los cuidadores es aún incipiente.

Métodos. Se utilizó una submuestra de conveniencia procedente de un estudio de mayor envergadura en Lisboa. Con este propósito, se evaluó transversalmente a una muestra de 50 cuidadores de pacientes aquejados de demencia (de tipoAlzheimer, vascular y mixta), utilizando el Dementia Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ), el GHQ-12, la escala de Sobrecarga del Cuidador de Zarit, la Positive Aspects of Caregiving Scale y parte del Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly.

Resultados. El 68% de los cuidadores eran mujeres, edad media 51, 7 (DT 13, 9) años. El grado de información y las necesidades relacionadas resultaron ser aceptables. En torno a la mitad de la muestra obtuvo una puntuación GHQ positiva. Las puntuaciones GHQ correlacionaron positivamente con las mediciones de sobrecarga, pero no se encontró asociación con DKQ. La sobrecarga y los aspectos positivos de la función de cuidador no se asociaron con el grado de conocimiento de los cuidadores.

Conclusión. Aunque estos resultados no son extrapolables, el hecho de estar informado no parece proteger del sufrimiento psicológico. Se valoró que estos cuidadores se encontraban en situación de riesgo.

Abstract

Aims. Links between disease-related knowledge, psychological distress and caregiving experiences in relatives of elderly demented people have been explored, although several issues remain unanswered. We aimed to study these dimensions in Portuguese relatives of dementia sufferers. Questionnaire validity was additionally ascertained. In Portugal, although scarcity of valid and reliable measures has been addressed, dementia caregiving research is still incipient.

Methods. We considered a convenience sub-sample from a larger survey in Lisboa. For this purpose, 50 carers of outpatients with dementia (Alzheimer, vascular and mixed subtypes) were cross-sectionally assessed, using the Dementia Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ), the GHQ-12, the Zarit Burden Interview, the Positive Aspects of Caregiving Scale and part of the CANE.

Results. 68% of these carers were female and mean age was 51, 7(SD13, 9) years. Information levels and related needs were widely acceptable. About half of the sample scored GHQpositive. GHQ scores were directly correlated to burden measures but no relation with DKQ results was found. Burden and positive aspects of caregiving were not associated with carers’ knowledge.

Conclusion. Although these findings lack generalizability, being informed does not seem to protect from psychological suffering. These carers were found to be at risk.

Background

Dementia (either Alzheimer’s Disease or not) and related caregiver burden are increasingly recognized as public health problems 1. In what concerns the informal caregiving experience, several dimensions have been described and addressed in research and in clinical interventions. These dimensions include not only caregiver burden (mostly a family affair in Mediterranean countries such as Portugal) but also psychological distress and the harder-to-value positive aspects of caregiving 2. So the caregiving experience remains a complex and challenging field for researchers and health practitioners.

For some years now, general education about dementia has been defined as a target from clinical, public health and users/caregivers’ point of view. In fact, irrational beliefs were shown to be predictive of depression and poor health 3. On the other hand, caregivers’ self-confidence and sense of competency, reduction of unrealistic expectations and increased use of positive comparisons seem to be more likely if accurate information was available and understood 4. Nevertheless, standards of information about the disease still remain low, especially wherever general health literacy levels must be developed, such as in low education populations. Lower knowledge standards have also been described in spouse caregivers, a finding deserving further exploration 5.

Links between dementia-related knowledge, psychological distress, caregiver burden and positive caregiving experiences in relatives of elderly demented people have been explored 4, 5. But these variables seldom were jointly considered. Much research remains to be done, also on account of somehow contradictory results. Knowledge was found to be positively related to anxiety but not to depression levels 4. Causal explanations call for prudence. For instance, following the same authors’ argumentation, it may be that higher levels of anxiety in knowledgeable carers may come from information acquisition and “anticipation of loss” phenomena. Or else anxiety-prone subjects may indeed be more prone to information seeking as well.

Proctor et al. 6 found that carers who were more knowledgeable on biomedical features of dementia and those adopting “monitoring for threat” coping styles were significantly more anxious.

Meanwhile, carers’ positive feelings toward caregiving were found to be positively associated with their level of well-being and negatively associated with the amount of burden imparted by the caregiving experience 7. In Portugal, although scarcity of valid and reliable measures has been addressed2, 8-11, dementia caregiving research is still incipient. To our knowledge, no study has consistently addressed relationships between information level and other caregiver characteristics among us.

Aims

We aimed to: 1) conduct an exploratory study on dementia-related knowledge, psychological distress, caregiver burden and positive caregiving experiences in Portuguese relatives of dementia sufferers; 2) ascertain further data on related measures’ validity.

Methods

Participants and sampling

We considered a convenience sample of 50 carers of elderly patients with a primary diagnosis of ICD10-Research Diagnostic Criteria of dementia (Alzheimer, vascular and mixed subtypes) from the first wave of the FAMIDEM project.

FAMIDEM stands as an acronym for Families of People with Dementia. The larger FAMIDEM survey is a comprehensive study of primary and secondary caregivers of demented elderly patients. Its second wave is about to be concluded (Gonçalves-Pereira M, Carmo I, Neves A, Santos L, 2006). Variables other than those specified below have been studied (such as coping and sense of coherence), but corresponding results are still being processed. Exclusion criteria for approached caregivers were: significant cognitive impairment or severe mental illness (acute state).

Setting

All caregivers were related to outpatients of an old age semipublic mental health facility in Lisboa or were in contact with family support activities carried out in that setting. Assessments were obtained at the outpatient clinic or were home-based, as convenient. Informed consent was obtained, also in order to publish data obtained during routine clinical assessments.

Design

This was a descriptive, exploratory study. Caregivers and patients were cross-sectionally assessed. Regarding this specific sample, all measures where administered by the first author. All carers approached agreed to participate and no one was excluded due to exclusion criteria.

Measures

Caregivers were given Portuguese versions of the Dementia Knowledge Questionnaire – DKQ 12, the twelve-item General Health Questionnaire – GHQ 12 13, the Zarit Burden Interview – ZBI 14 and the Positive Aspects of Caregiving scale – PAC 7.

Almost all respondents self completed the questionnaires and only 3 (6%) required significant help with the task. They were also interviewed in a semi-structured way in order to collect socio-demographic and clinical data, as well as to score the two carer-related items from the Portuguese version of the Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly – CANE 17, 18.

Validity and reliability of original versions of these measures have been thoroughly documented 7, 12, 14-17, 19, and GHQ or ZBI are well known in research and clinical settings.

The DKQ is a 7 item questionnaire covering four areas of knowledge on the subject of dementia (rudimentary knowledge – such as knowing that dementia is a brain disease and mostly affects elderly people; epidemiological knowledge – such as knowing that there are more than three dementia types and approximate prevalence ranges; clinical symptoms and aetiology). Each question has a choice of answers which includes a “do not know” option, therefore avoiding random guessing by respondents. Scoring is from 0 to 19 12.

The GHQ is a widely used brief screening instrument in general population mental health surveys, its 12 item version validity being grossly equivalent to extended versions. GHQ scores may be computed according to several methods 19: we used the Likert method, scoring each item from 0 to 3 and summing up a total score (range 0-36), as well as the original GHQ scoring process to define caseness. ZBI and PAC total scores were computed in a similar way (range 0-88 and 1-55, respectively), each item scored from 0 to 4 in the former and 1-5 in the latter questionnaire, so that higher scores mean higher burden or higher satisfaction with positive aspects of caregiving.

The PAC is a recently developed measure for the positive aspects of caregiving and one of the few that was found to be brief, valid and reliable. Its original version included eleven items and was subsequently simplified to a nine-item measure 7. Nevertheless, we decided to maintain the original structure as it has also been used in several high-quality surveys 16 and this would not put any obstacle to analysis nor represent a significant extra burden to respondents.

Portuguese GHQ-12 versions have been used 20, 21, but no cut-off points were clearly established specifically for Portuguese populations. Portuguese translations of DKQ (Gonçalves-Pereira, Almeida & Goulão, 2005), ZBI (Gonçalves-Pereira & Sobral, 2006)10, 22, PAC (Gonçalves-Pereira, 2005) and CANE (Gonçalves-Pereira, Fernandes, Leuschner et al. , 2005)18 were developed according to international conventions in order to ensure preliminary validity. In all cases, formal authorisation was obtained from the first author. Back translations were performed by an English native translator, also fluent in Portuguese and familiar with the mental health field. They were then revised by authors of the original questionnaires, with only minor corrections to be made. Furthermore, focus group discussion in carers settings was arranged for ZBI 10, 22 and PAC translations. There is another Portuguese translation of the ZBI which was unknown to us until its publication 11.

Patients were examined using a Portuguese version (Guerreiro et al, 1994) of the Mini Mental State Examination – MMSE 23, their autonomy classified using the Barthel Index 24 and behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia assessed with the Dysfunctional Behavioural Rating Instrument – DBRI 25.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and non parametric tests were used as required for analysis. All statistics were performed using SPPS.

Results

Caregivers’ socio-demographic characteristics and caregiving situation

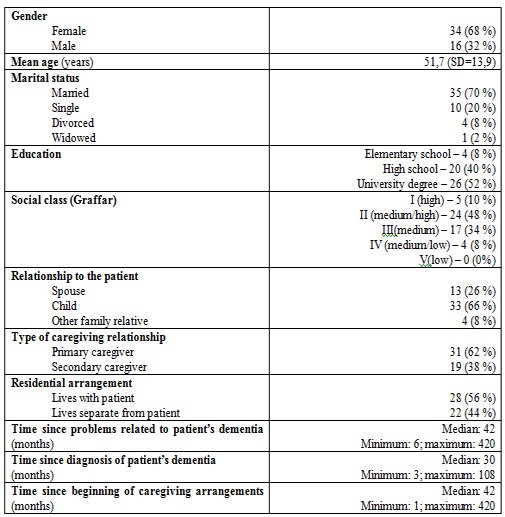

As can be seen in table 1, 68% of these carers were female and mean age was 51, 7 (SD=13, 9) years.

Table 1: Caregivers’ socio-demographic characteristics and caregiving situation

The majority of these participants (70%) was married and had over 12 years of education (52 %). Most of them were primary caregivers (62 %), lived in the same household as the patient (56 %) and were patients’ children. Caregivers living in the same household reported a mean weekly face-to-face contact with the patient above 36 hours. Only 5 carers were members of Alzheimer’s Associations, but did not attend regular self-help groups.

30 subjects (60 %) reported some sort of general medical condition, a cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease or arterial hypertension) in 12 cases.

23 (46 %) stated having suffered from psychopathological morbidity deserving clinical attention in the past. This was a depressive disorder in 15 (30 %) cases, the others being classified as anxiety states or other (one case of former substance dependence, one of psychosis in remission and one other of bipolar disorder, euthymic current condition).

Number of health consultations in the preceding 6 months ranged from 0 to 12, median 1. 19 (38 %) carers were not under any kind of treatment, although 18 (18 %) were taking psychotropics, mostly benzodiazepines, and 9 (18 %) were taking general medicines. One carer was currently on folk treatments.

Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics Patients’ median age was 78, 5 ranging from 62 to 96 years. Patients were mainly female, married or widowed and living in their own home. All were Caucasian.

The gross majority had a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease, the rest being vascular, fronto-temporal, parkinsonian or mixed subtypes. All somatic comorbidities (almost invariably present) were second-line in caring needs to the dementia condition, according to the sampling procedure.

The whole sample had contact with a mental health service, most were seen by a general practitioner as well and about half by a neurologist, albeit not in a regular way. About half were on treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors and one third with memantine. Cognitive remediation was a tool for only a small minority.

All patients scored as cases of significant decline in MMSE assessments (median 20), according to cut-off points defined for Portuguese populations, which are adjusted to educational levels. Barthel punctuations ranged from 15 to 100 (median 60) and DBRI scores ranged from 8 to 92 (median 33).

Caregivers’ assessments

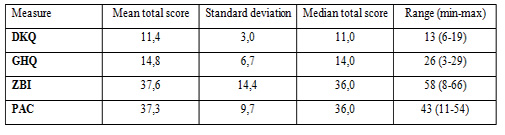

Tables 2-3 summarise results of DKQ, GHQ, ZBI, PAC and caregiver-related items of the CANE. GHQ scores were firstly computed according to the original scoring method. Adopting the 2/3 cut-off 19, 21, 28 (56 %) caregivers were defined as “GHQ positive”, i. e. probable cases of psychological morbidity (mainly anxiety, depression or mixed conditions). An almost coincident figure was obtained using the Likert scoring method and the 11/12 cut-off: 29 (58 %) caregivers scoring for probable caseness 19. All remaining GHQ scores in this paper were computed according to the Likert procedure.

Table 2: Participants’ knowledge about dementia, psychological distress and caregiving experience

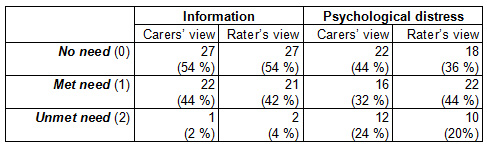

Table 3: Caregivers’ information and psychological distress needs

Bivariate analysis and comparisons between groups

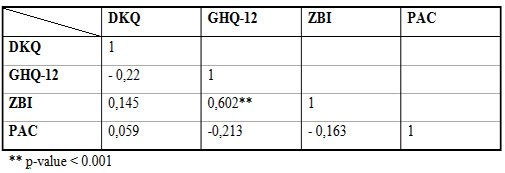

In order to explore bivariate linear associations between DKQ, GHQ-12, ZBI and PAC, nonparametric correlations were computed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Results are shown in table 4 below.

Table 4: Knowledge about dementia, psychological distress, burden and positive aspects of caregiving (correlation matrix)

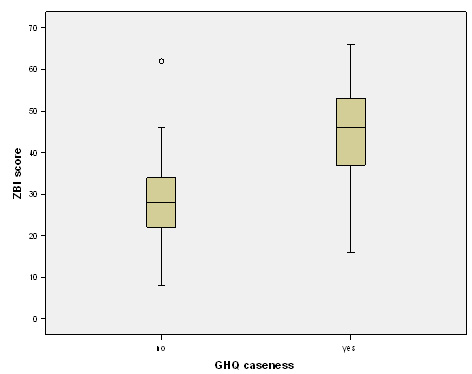

Furthermore, differences in DKQ, ZBI and PAC scores between GHQ-12 cases (GHQ+) and non-cases (GHQ-) were tested using Mann-Whitney test. DKQ scores were higher the GHQ+ group, but this difference failed to reach statistical significance (p=0. 423). On the other hand, in what concerns PAC, scores were lower (p=0. 047) in the GHQ+ group. Finally, ZBI scores were higher (p<0, 001) in the GHQ+ group (figure 1).

Figure 1: ZBI scores for GHQ cases and non cases

Discussion

This study presents interesting original results. All caregiver related measures were found to be ecologically valid in this Portuguese sample, as judged from total absence of missing items and refusals to complete assessments, as well as from the subjective impression of the field researcher.

Information levels and related needs were rather acceptable in this sample, when compared to other surveys 4, 5, 12, 18. Although not entirely in coincidence with the rater’s scoring, only a minor proportion of caregivers expressed unmet needs. High level of education of many participants surely contributed to this finding.

According to the literature, while there are different information needs across stages of the caregiving process, most carers state their preferred source of information to be a trusted health professional, backed up by some form of written information 26. In this sample, although a minority of caregivers had had previous access to psychoeducational packages, information had been disseminated most of all verbally for the majority of cases, during routine clinical procedures involving family members. This seemed encouraging as an outcome of mental health service delivery but that was not the case regarding carers’ psychological morbidity.

In fact, about half of the sample scored GHQ “positive”, GHQ cases being probable clinical cases of depression and anxiety. It is hard to discuss the causal role specifically assumed by the caregiving situation: a large proportion of participants also had psychiatric antecedents in which etiological explanations would be multifactorial. These would include a general vulnerability to stress, perhaps even biologically determined.

As expected, GHQ scores were directly correlated to burden measures (a moderate level and highly significant association) but no relation with DKQ results was found. This last result may confirm previous findings (depression being uncorrelated to high levels of knowledge about dementia)4 if our GHQ higher scores mainly accounted for depression. However, it may contradict results showing a positive association between DKQ scores and anxiety4, if our GHQ high scorers were mainly anxiety cases instead. In fact, GHQ should be sensitive enough to screen for clinical anxiety as well as for depression, but doesn’t allow to discriminate the two.

According to global PAC results, positive aspects of caregiving were valued by participants. This was so, no matter the important levels of burden and psychological distress simultaneously reported. Our results stress the importance of using discriminative measures for all these variables, namely in intervention trials. Burden and positive aspects of caregiving were not significantly associated with carers’ knowledge, either in direct or inverse ways.

The importance of addressing knowledge about dementia in routine clinical settings and caregivers’ surveys is beyond doubt. Family members are often the first to notice warning signs of impending dementia that may lead to early diagnosis and better secondary prevention 27. Besides, all those caring for patients with Alzheimer’s disease frequently face difficult decisions, either during everyday care processes or in more dramatic or particular circumstances such as deciding about instutionalisation.

This requires accurate problem-solving abilities in order to facilitate rational decision-making, which must be informed by sufficient knowledge about the dementia process 5. Moreover support and psychoeducational groups do not always match caregivers’ knowledge about dementia needs.

It seems crucial to understand associations among levels of dementia-related knowledge, its consequences for caregivers and their caregiving circumstances, as well as caregivers’ coping strategies. We were not able to equate coping in these specific results, although the larger FAMIDEM survey will provide further data on this.

Limitations

This non-randomised small convenience sample is surely biased in what concerns socio-demographic characteristics, being skewed towards high/middle income ranks. Indeed, the major limitation in this exploratory study (obviously precluding generalizability) is the fact that we unintentionally considered a non randomised sample where carers from a higher socio-educational background were indeed over-represented. Findings would probably be different in a more general population, and the larger and surely heterogeneous second FAMIDEM wave of participants will help to clarify this in an urban/suburban Portuguese population.

Nevertheless, on may argue that most subjects being able to provide self-completing questionnaires avoided interviewer-introduced bias in this study, contributing to assess overall validity and psychometric characteristics of caregiver measures.

Using a general screening measure as the GHQ-12 did not allow for discrimination of anxiety and depression. Furthermore, although there have been contributions to its validation in Portuguese populations 20, 21, defining caseness still must rely upon cut-off points that were not specifically tested and so must be adopted from culturally similar countries.

Issues to explore

Concerning general levels of knowledge about dementia, this study raises additional issues to be addressed. First of all, as a general issue and quoting Graham et al 12, these kind of studies highlight “the need for elderly mental health teams to evaluate their methods of dissemination of knowledge to carers, develop educational packages for carers and evaluate their effectiveness”. But above all, and according to Proctor et al. 6, research should further identify profiles of carers who are in need of education, in order to match individually tailored interventions to carers with specific information needs.

However, being informed did not seem to protect subjects in this study from psychological distress (although we were not able to discriminate anxiety from depression using a screening measure as the GHQ). Perhaps we should not rely so much in strictly informative psychoeducational packages if dissociated from more supportive or respite care components.

Conclusion

In spite of a huge amount of high quality research, the experience of caregiving in dementia remains a complex area.

In agreement with previous research, knowledge about dementia should be more systematically evaluated. The same applies to positive aspects of caregiving, which must be assessed in their own right even in the presence of heavy subjective burden and psychological distress.

Although our findings lack generalizability, being informed does not seem to protect by itself from the burden of care, nor from related psychological suffering. Carers in this sample, albeit presenting rather acceptable levels of knowledge about dementia and few related unmet needs, were found to be at risk.

References

1. Burns A, Rabins P. Carer burden in dementia. Int J Ger Psychiatry 2000; 15: S9-S13.

2. Gonçalves-Pereira M, Mateos R. A família e as pessoas com demência: vivências e necessidades dos cuidadores. In: Firmino H, Barreto J, Cortez Pinto L, Leuschner A, Eds. Psicogeriatria. Coimbra: Psiquiatria Clínica; 2006. p 541-560.

3. McNaughton M, Patterson T, Smith T, Grant I. The relationship among stress, depression, locus of control, irrational belief and health in Alzheimer’s disease caregivers. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1995; 183: 78-85.

4. Graham C, Ballard C, Sham P. Carers’ knowledge of dementia, their coping strategies and morbidity. Int J Ger Psychiatry 1997; 12: 931-936.

5. Werner P. Knowledge about symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease: correlates and relationship to help-seeking behaviour. Int J Ger Psychiatry 2003; 18: 1029-1036.

6. Proctor R, Martin C, Hewison J. When a little knowledge is a dangerous thing…: a study of carer’ knowledge about dementia, preferred coping style and psychological distress. Int J Ger Psychiatry 2002; 17: 1133-1139.

7. Tarlow B J, Wisniewski SR, Belle SH, Rubert M, Ory MG, Gallagher-Thomson D. Positive Aspects of Caregiving. Contribution of the REACH project to the development of new measures for Alzheimer’s caregiving. Res Aging 2004; 26(4): 429-453.

8. Martin I, Paul C, Roncon J. Estudo de adaptação e validação da escala de avaliação de cuidado informal. Psicologia, Saúde e Doenças 2000; 1(1): 3-9.

9. Brito, L. A saúde mental dos prestadores de cuidados a familiares idosos. Coimbra: Quarteto; 2002.

10. Gonçalves-Pereira M, Mateos R. Assessing Family caregivers: a necessary step towards comprehensive interventions with families of the demented elderly. Proceedings of the European Regional Meeting - International Psychogeriatric Association: 2006. Lisboa May 3-6. Psiquiatria Clínica, 2006. p 47.

11. Sequeira C. Cuidar de idosos dependentes. Coimbra: Quarteto; 2007.

12. Graham C, Ballard C, Sham P. Carers’ knowledge of dementia and their expressed concerns. Int J Ger Psychiatry 1997; 12: 470-473.

13. Goldberg D, Williams P. A user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-NELSON; 1988.

14. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feeling of burden. Gerontol 1980; 20: 649-55.

15. Zarit SH, Todd PA, Zarit JM: Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: a longitudinal study. Gerontologist 1986; 26: 260-266.

16. Boerner K, Schulz R, Horowitz A. Positive aspects of caregiving and adaptation to bereavement. Psychol Aging 2004; 19(4): 668-675.

17. Reynolds T, Thornicroft G, Abas M, Woods B, Hoe J, Leese M et al. Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly. Development, validity and reliability. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176: 444-452.

18. Gonçalves-Pereira M, Fernandes L, Leuschner A, Barreto J, Falcão D, Firmino H, Mateos R, Orrell M. Versão portuguesa do CANE (Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly): desenvolvimento e dados preliminares. Revista Portuguesa de Saúde Pública/Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública 2007; 25(1): 7-18.

19. Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, Ustun TB, Piccinelli M, Gureje O et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med, 1997; 27: 191-197.

20. Carochinho JA. Estudo de adaptação e validação do GHQ-12 de Goldberg para a língua portuguesa e considerações sobre a sua utilização em estudos ocupacionais. Proceedings of the XI International Conference Avaliação psicológica: formas e contextos (Machado C, Almeida L, Guisande MA, Gonçalves M, Ramalho V, Eds. ): 2006; Braga. Psiquilíbrios, 2006. p 257-267.

21. McIntyre T. Developing occupational stress research in a southern European country: a case study on Portuguese health professionals. Proceedings of the EAOHP Conference 2004. Maia, 2004.

22. Gonçalves-Pereira M. Dados preliminares sobre a validação da escala Burden Interview (Zarit e col, 1985) em Portugal. Proceedings of the 20th Meeting of grupo de Estudos do Envelhecimento Cerebral e Demências: 2006 Jun 23-24; Tomar, 2006).

23. Folstein MF, Folstein S, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12: 189-98.

24. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J 1965; 14: 61-5.

25. Molloy DW, McIllroy WE, Guyatt GH, Lever JA. Validity and reliability of the Dysfunctional Behaviour Rating Instrument. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84: 103-106.

26. Wald C, Fahy M, Walker Z, Livingston G: What to tell dementia caregivers – the rule of threes. Int J Ger Psychiatry 2003; 18: 313-317.

27. Cruz VT, Pais J, Teixeira A, Nunes B. Sintomas iniciais de doença de Alzheimer – a percepção dos familiares. Acta Med Port 2004; 17: 437-444.

IMPORTANTE: Algunos textos de esta ficha pueden haber sido generados partir de PDf original, puede sufrir variaciones de maquetación/interlineado, y omitir imágenes/tablas.

BLACK FRIDAY COMPULSION

Jesús de la Gándara Martín

Fecha Publicación: 04/12/2025

Consejos Prácticos para el Cuidador del Paciente con Demencia.

JANIER RAMIREZ RODRIGUEZ

Fecha Publicación: 20/09/2025

Deterioro cognitivo leve: concepto, subtipos y neuropsicología clínica

Iván Zebenzui Moreno González et. al

Fecha Publicación: 18/05/2025

Trastorno Obsesivo-Compulsivo y Demencia

Roberto Fernández Fernández

Fecha Publicación: 18/05/2025

Benzodiacepinas y alteración de la arquitectura del sueño: ¿Un factor de riesgo para la demencia?

Marc Moreno Blanco et. al

Fecha Publicación: 03/03/2025

De cuidados a cuidadores: ¿de disociación, desestimación o forclusión se trata?

Mónica Beatriz Peisajovich

Fecha Publicación: 20/05/2024